Ruins are ubiquitous in the African continent. These ruins can be of a collapsed regime, mode of living, or the debris of contemporary projects related to “Africa rising” discourses (McKenzie 2016). They can also stem from past colonial interventions, modernisation, development projects, socialism, neoliberalism, and other political regimes resulting in disruptions in the natural, social, political, and cultural realms that constitute today’s lives in the continent. Such disruptions are further intensified and caused by climate change, which some scholars have proposed to call the Anthropocene to foreground the fact that humans have become a major force shifting the Earth’s climate away from the Holocene (Crutzen 2006) resulting in extreme weather events, biodiversity loss, and a planetary crisis, which affect mostly poor countries.

As Ann Stoler reminds us, “[…] ruination is more than a process that sloughs off debris as a by-product. It is a political project that lays waste to certain peoples, relations, and things that accumulate in specific places (Stoler 2008, 11). The Anthropocene nature, the built environment, and its peripheries are all in fact, active archives (Tsing et al. 2017; Lyons 2020) that evidence histories of violence (Nixon 2011) and loss (Harvey 2017). These political projects have left and are still leaving ruins. Some of these traces are appear and others invisible, and impose new topographies, temporalities, and subjectivities. While we are reminded that ruination results in geographies of exclusion, marginalization, displacements, and degradation, we also underscore, that the effects of ruination also invite us to look at them as spaces of creativity and political mobilization (Edensor 2005).

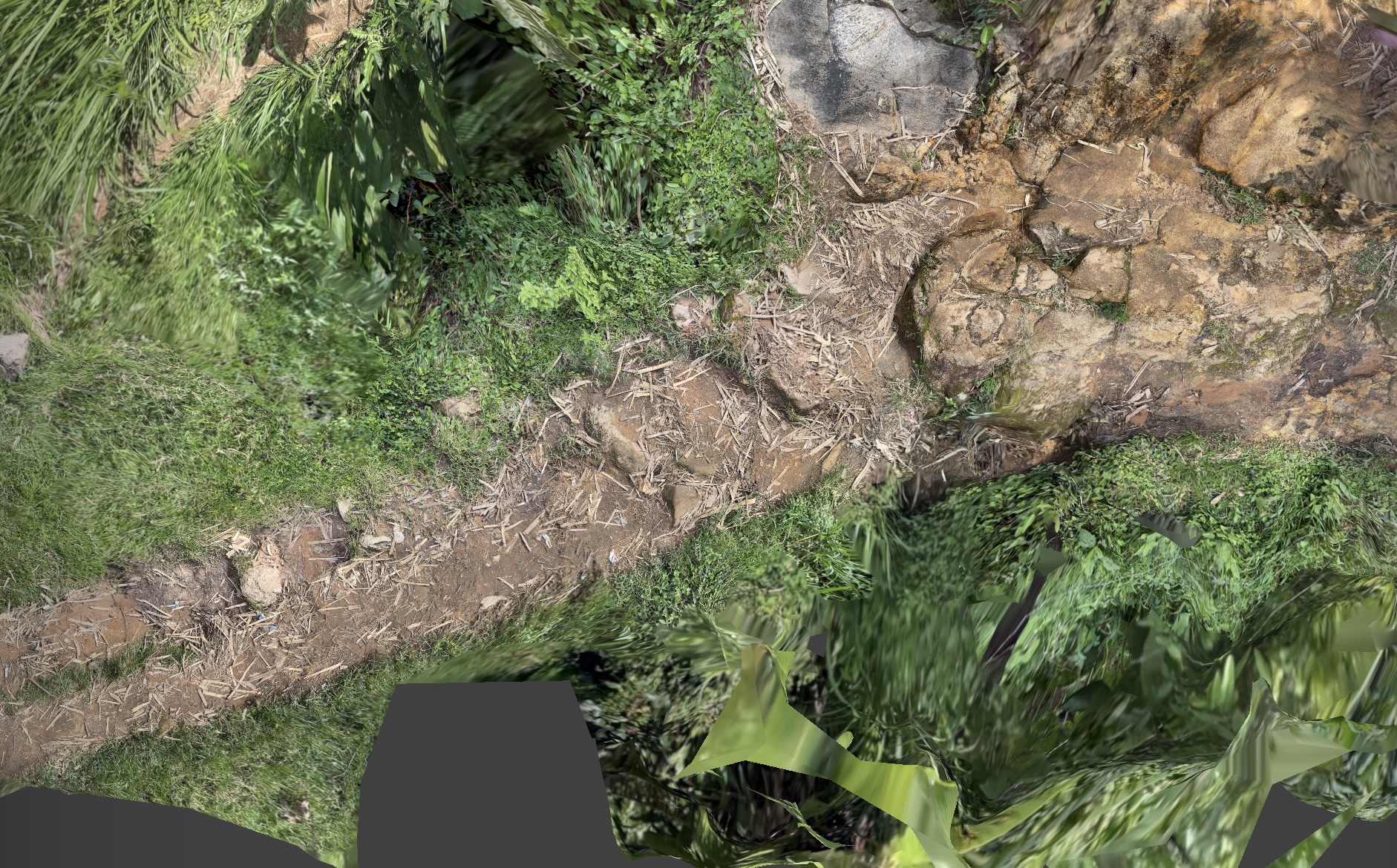

Africa’s ruined landscapes call for a close examination and documentation of the numerous remains of various political projects. Here we emphasise what Anna Tsing calls the “arts of noticing” that make visible the complex web of relations between all elements of life (Tsing, 2017). To accomplish that, we believe that a critical understanding of our problematic inheritances —here also referred to as traces—is needed.

“Tracing” has various meanings. A trace can be a mark that was made by a recording device such as GIS, a camera, a voice recorder, carbon dating, a microscope, etc., or by something that already passed, a sign or evidence of some past thing (1) that persists. A trace can be read as a brief period, a minute, moreover, it can be material and immaterial. “Tracing,” in contrast, is an active foraging of marking the remains, intentionally highlighting the significance from the surface. Tracing is engaging with the present and having multiple worlds prevailing. Tracing is not only about recording the manifestation of the past in the present but is also a form of communicating and political engagement.

The panel also seeks to showcase the ways of researching beyond sight, as many fragments of knowledge are not easily seen. Grounded in environmental and interdisciplinary perspectives that consider the interconnectedness of ground, soil, water, air, and materials, this panel welcomes papers centred on employing creative methodologies to trace ruination. We aim to expand the methodological discourse, and by then to critically engage with our surroundings – unravel the layers of history that often go unnoticed. Through “other” practices, one can uncover the imprints of past events and human interventions on and with the landscape.

Footnotes:

(1) Merriam-Webster. n.d.. Trace. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved May 08, 2024, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/trace.

(2) Igwe works with her body, archives and narratives, both oral and textual, acting as a mode of enquiry that makes possible the exposition of overlooked histories. Her film from 2020, No Archive Can Restore You, engaged with the former Nigerian Film Unit building in Lagos and its particular state of decay.

(3) In his film Uppland, he explores the invisible, beyond the colonial frame, using memory, voice and absence to reveal the present deprivations of Yekepa, an abandoned mining town in Liberia.

(4) African Digital Heritage is a Nairobi-based non-profit organisation working to advance a more critical approach to digital solutions within African heritage. africandigitalheritage.org